When it was first announced that Leonard Cohen was coming to Charlottetown to play one night - May 18, 2008 - I didn’t even consider going as I knew I was going to be off-Island. But if I had, I would have been terribly disappointed: the Homburg Theatre at the Confederation Centre of the Arts, which holds 1,102 people, sold out at $72 a pop in a record 52 minutes. To add insult to injury, so many people tried to buy tickets online that they crashed the Confed Centre’s website. It was unheard-of.

I consoled myself with the fact that maybe he’d be playing in Vancouver while I was there, but alas he was not… and I only got to hear the reviews from friends: “a phenomenal concert,” “the best I’ve ever been to,” “the old guy still has it,” “he sang for over three hours without a break,” “his back-up singers and band were fantastic,” “what a professional,” “he’s still got what it takes.” Hmm… Jealous? Yup.

And then there was the Leonard Cohen tribute concert in April in Victoria, organized by my friend Henry Dunsmore because he was one of the many disappointeds who couldn’t get a ticket. It was a memorable night, where so many of Leonard’s songs came alive for me, sung by friends of all ages, with the fabulous house band of Jon Rehder, Remi Arsenault, Reg Ballagh, Michael Mooney, and Peter Bevan-Baker. It was especially wonderful because it was the first time Mike and I sang together in public – me with “Suzanne” and him with “That’s No Way to Say Good-bye,” backing each other up with harmonies. Sigh…

Little did I know then that I’d get my chance to see the real Leonard Cohen only months later. Not in Charlottetown, Halifax, or Vancouver, but in Hobart, Tasmania. It was The Leonard Cohen World Tour 2010.

I can’t remember where I first heard that he was coming – but it was pretty soon after I had arrived. I went online to see if I could get tickets, but the cheap ones ($139!) were gone. And as much as I wanted to see this Canadian poetry icon, I couldn’t justify a $194 “good seat” – not on a student’s budget. Pete’s wife Anna suggested I might be able to find a cheaper ticket by checking out the classifieds in the Mercury (the local paper) – but in the end, it was word-of-mouth, the most powerful purveyor of information, that got me there. I happened to mention all this to Ralph Wessman (publisher of Famous Reporter and Walleah Press) and Jane Williams (poet extraordinaire) on the drive to Launceston for the Poetry Festival in early October. From the driver’s seat Ralph piped up that an e-mail had just come around his office that day – apparently someone from Canberra had bought two of the expensive tickets for himself and his partner. When he went home and said, honey, guess where we’re going November 15, she said, honey, I don’t like Leonard Cohen. (I’m thinkin’ that might be grounds for divorce in my house!) So he was trying to sell hers for $150. I said to Ralph: please send me his e-mail address! So on Monday, he did; I fired off an e-mail; and Andrew in Canberra said sure, you can have it… see you on the 15th. He put the ticket in the mail; I transferred money into his account; the ticket arrived; I showed it off to my fellow students at Tuesday tea and cake time. Then he decided to sell his ticket, too. Turns out he could get to the concert at Hanging Rock (yes, an outdoor concert on Nov. 20 under the stars at the iconic Hanging Rock!) more easily than coming to Tasmania (after all, we ARE an island here!). I sent around an e-mail to the Geography Department saying there was another ticket available, and it went, too.

I knew that Pete and Anna, along with their friends Derek and Jan, had bought their tickets six months ago… so I boldly asked if I could hitch a ride with them. They said sure – so we left Monday after work to drive to the Derwent Entertainment Centre (an arena-type venue that seats 5,000) a short distance outside the city. Anna suggested that we go early to beat the traffic, and have a picnic supper. Of course it was raining, so we sat in lawn chairs underneath an overhang by the utility entrance and had Anna’s marvelous salmon quiche, Jan’s salad made with greens from their garden, Laurie’s chocolate cupcakes (surprise, surprise), and some wine from Stewart’s wine cellar (he told me I could help myself, really!).

When the doors finally opened, the rest of my happy party went in one direction and I went off on my own to find my seat. I felt just like I did boarding the Icelandair flight in New York City to discover that I was in Business Class: my seat was fantastic! I was down on the main floor, seven rows from the front, and right in the middle. I waved to my friends in the nosebleeds… After a while the woman who bought Andrew’s other ticket came along: Anne Hughes. Of course she knew Pete and Anna (after all, this IS an island!). Her musician partner and Pete had collaborated on some music and poetry events in the past. We marveled at our good fortune, and she said she quite enjoyed getting to know our ticket seller. He told her to watch out for the homesick Canadian who would be sitting next to her…

Before settling in to my seat, I wandered around a little, checking out the stage and the merchandise...

When one of the ushers noticed I had purchased some of the merchandise, we struck up a conversation. She told me that a group of 22 teenagers were sitting just behind where we were standing. So, curious as to why such young kids would be there, I went over to talk to them. Apparently they had written a fan letter to Leonard Cohen, telling him that they play some of his songs in their band at school. So Cohen’s manager wrote back from Beverly Hills – and offered them 22 free tickets. Talk about class! The kids, from Eastside Lutheran College (along with a couple of dad chaperones), could hardly sit still – they were THAT excited. They said that “Hallelujah” was their favourite.

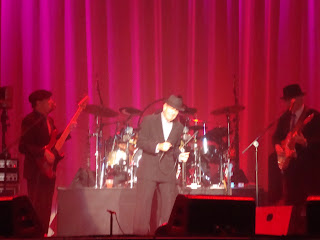

So... what can I say? The concert was amazing. Leonard came out in his signature fedora and black suit, and from the moment he opened his mouth to sing “Dance Me to the End of Love,” he had us in his the palm of his hand. His voice is just as deep and gravelly as it ever was, his lyrics as poignant. He plays guitar on several of his songs, and a tiny preprogrammed electric piano on one. (He joked that he doubted that anyone else had that kind of technology…) At the age of 75, he can get down on his knees to sing – and back up again without missing a beat – which he did regularly. It was especially touching when he knelt in front of his guitar/bandurria/laud/archilaud-player, Javier Mas from Spain, or sang with and to his musical collaborator and back-up singer Sharon Robinson (who co-wrote and produced his 2001 album, Ten New Songs), and to Charley and Hattie Webb, his other two singers. (I want to be a back-up singer when I grow up. Although I’ll never be able to do cartwheels in tandem like they do!) He interacted with everyone on stage, and twice introduced – or, rather, paid homage to - each of them with descriptors that only Leonard the Poet could pull out of his black fedora: sublime, impeccable, high priest of precision, shepherd of strings, signature of steady, architect of the arpeggio...

Even though they’ve been doing the show for three years, and this is their second time through Australia, the act was fresh and exciting. He even mentioned "Hobart" in one of the songs, so the audience knew that he knew where he was... You could tell that everyone in the band loved being on stage with him, and Leonard’s appreciation for them was obvious. Indeed, an article in one of the papers talked about the family atmosphere he creates, and the mutual respect they each have for the other – Leonard treats them like equals. And it shows.

The first half of the show was great, but it wasn’t until after the intermission that I found myself engaging emotionally. Sure I was excited to be in the presence of a Canadian poetry icon... and to be with other like-minded people so far away from Canada was amazing... But I didn't feel that real connection with the music until after the break. The second half was simply fantastic. Maybe the songs were more upbeat, or maybe they were all really getting into the groove. There wasn’t much banter – and what there was was poetry. Real Leonard Cohen poetry. Spoken by Leonard Cohen. Like the way he did “A Thousand Kisses Deep.” It made me remember kisses. How good they can be.

Sharon Robinson did Boogie Street, with Leonard and the rest of the band doing back-up. Dino Soldo, “the master of breath,” who plays all the wind instruments – and on this song a soulful saxophone that brought much applause - was totally in awe of her performance, pushing back all the accolades to her. And the Webb Sisters did a gorgeous duet in one of the THREE encores. Leonard bounded on the stage at 8:15 p.m., and bounded off at 11:40 (with “Closing Time”), with a 20-minute break in the middle. Stamina or what…

I can’t say that it’s the absolute best concert I ever went to – but then I'm hard-pressed to name the best concert I ever went to. (Maybe Billy Joel when I was 18 and my ex-boyfriend bought me a ticket – one ticket – so I had to go on my own to the Vancouver Coliseum… memories of that experience no doubt mixed up in memories of cruel teenage love gone wrong…) But Leonard Cohen would be a close second for me. I just wish my sweetie, who bought me the ticket for my birthday, had been able to share the magic, too! (I bought him a T-shirt… I know, I know, such a cliché…)

Here’s the set list, courtesy of Maarten Massa...

FIRST SET

Dance Me To The End Of Love

The Future

Ain’t No Cure For Love

Bird On The Wire

Everybody Knows

In My Secret Life

Who By Fire

The Darkness

Chelsea Hotel #2

Waiting For The Miracle

SECOND SET

Anthem

Tower Of Song

Suzanne

Avalanche

A Singer Must Die

Sisters Of Mercy

The Gypsy’s Wife

The Partisan

Boogie Street

Hallelujah

I'm Your Man

A Thousand Kisses Deep (poem)

Take This Waltz

FIRST ENCORE

So Long, Marianne

First We Take Manhattan

FINAL ENCORES

Famous Blue Raincoat

If It Be Your Will

Closing Time

|

| Photo from the souvenir program (Dominique Issermann) |